खोनसाइ

KHONSAY: POEM OF MANY TONGUES

The Poem in Depth

Text – Sources – Links – Background

खोनसाइ (Khonsay): to pick up something with care as it is scarce or rare. (Boro language, Devanagari script, India)

Introduction

“There are nine different words for the color blue in the Spanish Maya dictionary, but just three Spanish translations, leaving six [blue] butterflies that can be seen only by the Maya, proving that when a language dies six butterflies disappear from the consciousness of the earth.”

- Earl Shorris

Poetry, then, is precisely what is least translatable about a language – it is the ineffable, the things that only a set of words in a particular language can say. Translated into English from many languages, “Khonsay” is an act of audacious and unabashed imagination. It imagines the ecology of languages through a world poem. It seeks to capture the luminous originals in refracted light. The voices of the indigenous speakers draw us in, even if non-speakers do not understand what is being said. Yet what cannot be translated, what we cannot do justice to, is a measure of what is being lost as so many languages disappear.

Though definitions differ, poetry exists in every culture: the crystallization of experience into words, word into art, the engaging patter of consciousness itself. “Khonsay” is a tribute and call to action to support the diversity of the world’s languages. The poem is a “cento,” a collage poem; the name in Latin means “stitched together,” like a quilt — each line of the poem is drawn from a different language, appearing in that language's alphabet or transliterated from the spoken word, followed by an English translation.

the poem

PROLOGUE

(1) Ch’a tlákwdáx si. áat, tlél ch'as yá táakw

It didn't just start yesterday

—Nora Marks Dauenhauer (Tlingit, Alaska, U.S.)

This line, written originally in Chinese by Han Shan (c. 800 AD) and here in Tlingit, comes from Nora Marks Dauenhauer’s experimental translations into Tlingit from a variety of origins and poetic styles. Dauenhauer was born in Juneau, Alaska in 1927. She was monolingual in Tlingit as a child, adding English when starting school. As an anthropologist and an award-‐winning poet and writer, she has contributed to safeguarding the Tlingit language through fieldwork, transcription, translation and explanation of oral literature. Tlingit is spoken by about 600 people today in Southeast Alaska and Western Canada.

(2) Li' to bu nakal le jme'tike

Come to the source of the word

—Alberto Gómez Pérez (Tsotsil, Mexico)

Gómez Pérez was born in 1966 in Ejido Santa Catarina Las Palmas in Chiapas, Mexico. He writes poetry, narrative, and essays, and his poetry publications include “Words for the Gods and the World,” “May the Sun Not Fade Away,” and “The Weeping of Times.” This line is from his poem “Yibelun k'op/ Source of the Word,” translated by Donald Frischmann. Tsotsil (also Tzotzil) speakers call their language Batz’I K’op/ true language. At the end of the 20th century there were more than 514,000 speakers of this Mayan language, living primarily in the municipality of Chiapas.

(3) Namawi ruwi, namawi tapatawi ponun wanyil

namawi thunggarar tumbiwalunngayambun

Our land, our waters are dying

but our language is coming to life again

—Tumake Yande Aboriginal Elders Group (Ngarrindjeri, Australia)

This line is written and translated by Tumake Yande Aboriginal Elders Group, a governmental aboriginal healthcare program serving aboriginal elders and their care givers living on Ngarrindjeri Lands. Ngarrindjeri (also Narrinyeri) is listed by the Ethnologue as spoken by 160 people in 2006 in South Australia and nearly extinct. The language is being revived by enthusiasts, supporters, and a responsive community, restoring speaking in full sentences in speeches at community events and through songs and stories. Language speakers have generated teaching materials for children and adults, including a dictionary.

(4) We:s ha'icu 'at hahawa ‘i-hoi

Everything is now moving and alive

—Ofelia Zepeda (Tohono O'odham, Mexico)

This line is from the poem “Rain” by Ofelia Zepeda (b.1952), a poet, linguistics scholar, and cultural preservationist, whose poetry touches on linguistics, O’odham traditions, the natural world, and the experience of contemporary O’odham life. Zepeda directs the American Indian Studies Program at the University of Arizona as well as the American Indian Language Development Institute, which she co-founded. Tohono O'odham is spoken by about 14,000 Tohono O'odham Native Americans in the U.S. and Mexico.

(5) Fonua, kelekele/ kakai/ anga fetu'utaki,

Land. People. Connection.

—Vaimoana Niumeitolu (Tongan, Tonga)

Tongan is the national language of Tonga, which occupies an archipelago of 176 islands in the southern Pacific Ocean, 52 of which are inhabited by about 100,000 people. Vaimoana (Moana) Niumeitolu is a Tongan-American poet, actor, and painter. She is an advocate of peace, joy, love, cultural awareness, and artistic expression, and the founder of Mahina Movement, a trio of poets and musicians who perform and tell stories about individuals, like themselves, who deal with dual identities. Translation by Va'eomatoka Valu and Elisiva Maka.

WELCOME

(6) Iyeh tubabolu nata luntamba. Luntamba jalimussow ning jalikewolu,

tubabolu nata. Luntamba jarra, Luntamba!

Our guests have arrived

Welcome to our house, and feel at home

—Women from Papa Susso Family (Manding, Gambia)

Manding (or Mandinka) is one of the Manding Languages, and is spoken in Mali, Senegal, Gambia, Guinea, the Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau, and Chad by about 1.4 million people and recognized officially only in Senegal. It uses Latin and Arabic–script based alphabets. The Arabic–based alphabet is widely used, older, and associated with Islamic areas, while the Latin one, introduced and spread after colonization, is the official one. This welcome line was sung by women in the Papa Sasso Family in Banjul, Gambia, and translated by Papa Susso.

(7) Mai cumin-ange, ewa’ilan, Apo’ nimena’ in tana

Come eat, o mighty god, ancestor

Who has cultivated the earth

—Alfrits Monintja (Tontemboan Minihasa, Northern Sulawesi)

Tontemboan is an Austronesian language, of northern Sulawesi, Indonesia, with a ‘threatened’ status. As of 2013, an estimated 100,000 people speak the language, but it is not being passed on to children and is under pressure from Manado Malay, a creole of Malay. Documentation of Tontemboan assembled by missionaries a century ago is relatively inaccessible to its speakers, as it is written in the Dutch language. Alfrits and his wife Rose settled in Queens, New York via Jakarta from their thousand-person village, and have taken part in readings at the Bowery Poetry Club held by the Endangered Language Alliance.

(8) Mapia y pattolay tawe ta ili mi,

cunnasimaggarammammu kami

Life is beautiful in my village,

Everybody knows everyone here

—Grace G. Baldisseri (Ibanag, Philippines)

Ibanag is spoken by about 500,000 people in the Philippines, as well as by Filipino immigrants in the Middle East, the UK, and the U.S. The line is from a poem titled “Tawe Ta Ili Mi/ In My Village,” written and translated by Grace G. Baldisseri, who lives in the U.S. and writes poetry in English and Ibanag. Since 2012, the revival of Ibanag culture has become part of the Mother Tongue-based program of the Filipino government, which seeks to preserve indigenous cultures, including languages.

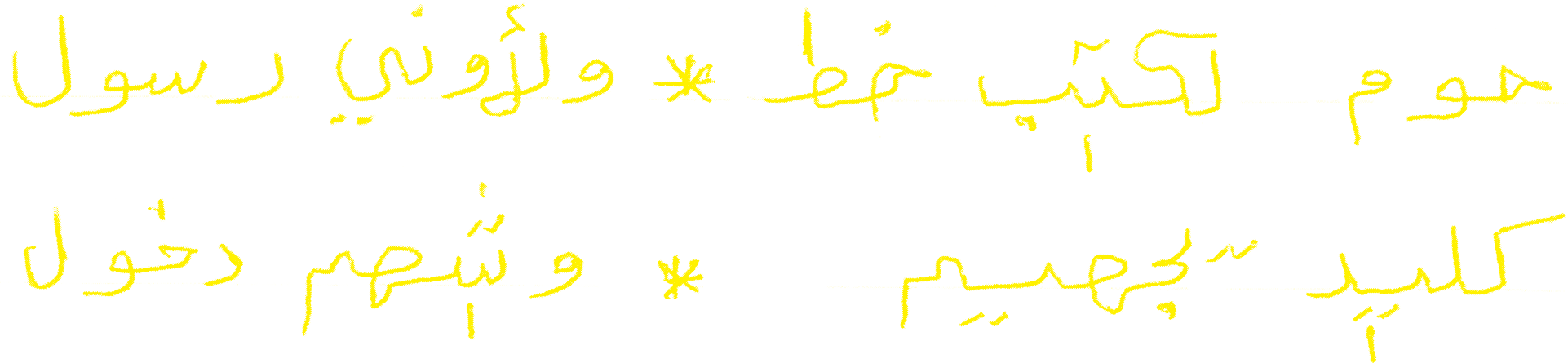

(9)

I want to write a line and hire a messenger

Who has an entry visa

—Hajj bir Ali bir Dakon (Mahri, Yemen)

Mahri (also Mehri) is spoken by about 115,000 people in Yemen and Oman and is a remnant of the indigenous languages spoken in the southern Arabian Peninsula before the arrival of Islam to the region and the Arabic language that came with it. Mahri is primarily oral. The line was written by Hajj bir Ali bir Dakon using a slightly modified Arabic script, and translated by Sam Liebhaber. His published poetry marks a milestone in writing Mahri, which has several dialects, and has not been written before.

(10) Hokšey Himhen, ‘uTThin, kaphan, Hokšey

Kiš Horše ‘Ek-Hinnan

Jump! 1, 2, 3, Jump!

My heart is good (Thank you)

—Vincent and Gabriel Medina (Ohlone, Northern California)

The Ohlone languages, also known as Costanoan, are a small family of languages of the San Francisco Bay Area spoken by the Ohlone people. A 2009 study estimates that there is only one remaining native speaker, but language revitalizaton efforts are underway. The Ohlone languages were all extinct by the 1950s. However, today the dialects of Mutsun, Chochenyo and Rumsen are being "revitalized" (relearned from saved records). Vincent Medina is a poet, storyteller and language activist.

THREAT

(11) Mise an teanga i mála an fhuadaitheora

I am the tongue in the kidnapper’s sack

—Gearóid Mac Lochlainn (Irish, Ireland)

Even though the Irish government published its “20-Year Strategy for the Irish Language” in 2010, the Ethnologue continues to list Irish as threatened. It was the main language in Ireland until the 18th century, when it lost ground to English for political and economic reasons. This line is from a poem titled “Teanga Eile/ Second Tongue” by award-winning poet Gearóid Mac Lochlainn, and translated by him and Séamas Mac Annaidh. Mac Lochlainn has chosen the path of being a poet who writes in an endangered language in the 21st century, even though it may limit his audience drawing economic difficulties.

(12) Kupfa kwabo kwana twalaga mihizo yako Banyindu balike lama mu miira Ndeto yetu yana gendaga I gandagala.

When the old ones died, the Binyindu stories died

Our language keeps collapsing

—Michel Musombwa Igunzi (Kinyindu, Dem. Republic of Congo)

Located in the east of the Democratic Republic of Congo are the Nyindu indigenous people. Of the 2,000 speakers of Kinyindu, only approximately 10% of Nyindus are considered fluent in Kinyindu. While the average age of these speakers is 40 years, the war-ravaged circumstances of the DRC create a life expectancy of only 46. Michel Musombwa Igunzi received funding from the Endangered Language Fund to organize the Association for the Survival of the Cultural Heritage of the Nyindu Indigenous People, ASHPAN, and with Mazambi Wikaliza of the Pedagogical Superior Institute was able to compile a Kinyindu Endangered Language Lexical Data Base. In an effort to revitalize the language, the project aims to produce the first bilingual database in Kiswahili and Kinyindu.

(13) Desten nou

Se pa pou nou fini mal

Our destiny is not to have an unfortunate end

—Denize Lauture (Haitian Creole, Haiti)

A creole arises when a pidgin, a simplified language, developed by adults for use as a second language, becomes the native and primary language of their children. Haitian Creole, or simply “Creole,” is the official language of Haiti along with French, and is a mixture of French and African languages and dialects. This line is from the poem “Desten Nou/ Our Destiny,” written and translated by Denize Lauture. A poet and short story author, Lauture (b.1946) writes in Creole and English.

(14) ’Au'a 'ia, e Kama e, kona moku, 'O kona moku, e Kama, e 'au'a 'ia

Hold fast to your island child,

To your island child, hold fast

—Keaulumoku (Hawaiian, U.S.)

This line is from a chant by Keaulumoku predicting the overthrow of the Hawaiian religious belief systems. It is a very famous mele hula today. “Mele” means “song” in Hawaiian, and “hula” is a dance form developed by the Polynesians who originally settled in the Hawaiian Islands, and based on a chant or song. Hula dramatizes or portrays sung words in visual dance form. This hula is danced with a pahu or sharkskin drum. It was translated by Puakea Nogelmeierin in consultation with Aunty Pat Bacon. Keaulumoku is the first and perhaps oldest-known Hawaiian chanter.

ANCESTORS

(15) Tilli pa yue te gbong

The ladder gave the roof its name

—Anbegwon Atuire (Buli, Ghana)

This proverb in the Buli language of northern Ghana comes from the oral tradition of the Builsa people, and was collected and translated by Awon Atuire. Buli is spoken by about 150,000 people and classified by the Ethnologue as developing, which means that it is in vigorous use, with literature in a standardized form being used by some, although not yet widespread or sustainable.

(16) Yageya

Yageya, My name is Yageya. It means, “She remembers.”

—Maria Hinton (Oneida, NY USA)

Oneida is an Iroquoian language spoken primarily by the Oneida people in the U.S. states of New York and Wisconsin, and the Canadian province of Ontario. There are an estimated 250 native speakers. Maria Hinton (1910-2013) was a Faith Keeper of the Oneida longhouse and one of the first state-certified Oneida language teachers in the country. Born into the Oneida language, Maria spoke fluent Oneida her entire life. She worked for over 20 years with her brother Amos Christjohn, Dr. Clifford Abbott, and others to preserve the language in an Oneida dictionary. She and Dr. Abbott would later adapt it into an online version, for which she spent nearly two years recording her voice. They completed the online dictionary in 2008.

(17) Uvumai apamai e'i aipa ivo'i kelogo

Uvumai apamai e'i kapulai kekapulaisa

Our ancestors were the source of daring

Our ancestors were the source of victory

—Efi Ongopai (Mekeo, Papua New Guinea)

Mekeo is mainly spoken in two villages in Papua New Guinea by about 20,000 people. Papua New Guinea has the most languages per capita than any other country, with over 820 indigenous tongues, representing 12% of the world's total; yet most have fewer than 1,000 speakers. This line is from a traditional Mekeo war song titled “Ivani Ivina,” collected by Allan Natachee in the 1940s from a Mekeo elder called Efi Ongopai, and translated by Lucy Isoaimo-Irish. Many Mekeo songs are war chants and dances where the singers accompany the songs, using spears and bows as rhythm sticks. The line is spoken by Ilona Rayan.

MYTH

(18) Ki heeltemaal llx’oßa ku ka-!qora

ka-!qora ka-!qora ka-!qora

The crack opened up and she kept

Playing, playing, playing, playing

—Griet Seekoei (N|uu, South Africa)

Nǁng or Nǁŋǃke, commonly known by its primary dialect Nǀuu (Nǀhuki), is a moribund Tuu (Khoisan) language once spoken in South Africa. It is no longer spoken on a daily basis, as the speakers live in different villages. Nǁng prospered through the 19th century, but encroaching non-ǃKwi languages and acculturation threatened it, like most other Khoisan languages. The language was mainly displaced by Afrikaans and Nama, especially after speakers started migrating to towns in the 1930s and found themselves surrounded by non-Nǁng-speaking people. In 1973 their language was declared extinct, but in 2013, three speakers of Nǀuu were established.

Christopher Collins is a linguist who has long worked with the N|uu language. The line spoken by Greeot Seekol, one of a few remaining speakers of N|uu, is from her story “The Jackal, His Wife, His Daughter and His Mother”. Recording by Dr. Collins.

(19) Kuningmulli Qiujaviit, Uqquulaamut Qiujaviit

His face is against the ground

Feeling cold, falling asleep

—Tanya Tagaq Gillis (Inuktitut, Eastern Canada)

Inuktitut (ᐃᓄᒃᑎᑐᑦ), also Eastern Canadian Inuktitut or Eastern Canadian Inuit, is one of the principal Inuit languages of Canada. It is recognized as an official language in Nunavut alongside Inuinnaqtun, and both languages are known collectively as Inuktut. The Canadian census reports that there are roughly 35,000 Inuktitut speakers in Canada, including roughly 200 who live regularly outside of traditionally Inuit lands. Tanya Tagaq Gillis a Juno Award-winning Canadian throat singer and popstar. Her album, Retribution, was released October 2016

(20) Mo tu’iei ta pepe si hie. Os’o tu einca:

Pa’so noyano ‘emo ookosi ci feango’u

The sun is smiling in the sky

And I say, Please warm my body

—Baitz Niahossa (Tsou, Taiwan)

Tsou is one of the 14 indigenous languages of Taiwan which spawned 90% of the Austronesian languages. Tsou is spoken by about 4,000 people in Mount Ali in Chia-Yi county of Taiwan. The language is not written; it is currently being passed on primarily by folk songs and folk tales.

Baitz Niahossa is a language and indigenous rights activist from Lalauya who is dedicated to teaching Tsou to children. This line is from a children’s song used in her languages classes. With Dan Kaufman of the Endangered Languages Alliance, she recorded elder family members and traditional leaders in the Ali-Shan Aboriginal Tsou Youth Choir, which has won awards for Tsou culture. The Youth Choir has been learning the language through performances of traditional Tsou music that Baitz has been transcribing, and they have been singing them in a modern style all over the world since 2001. Baitz’s father is currently writing a comparative study of Tsou dialects. The Tsou language struggle exemplifies the difficulties of the government’s efforts to commodify an endangered language.

(21) Turgun ai alin oci huwejehe huwejen, bira oci oboro oton

The mountain is my screen

The river is my washing tub

—Hoong Teik Toh (Manchu, China)

Manchu is a severely endangered Tungusic language spoken in Northeast China; it was the native language of the Manchus and one of the official languages of the Qing dynasty (1636–1911). Most Manchus now speak Mandarin Chinese. According to data from UNESCO, there are 10 native speakers of Manchu out of a total of nearly 10 million ethnic Manchus. The Manchu script is derived from the traditional Mongol script, which in turn is based on the vertically written pre-Islamic Uyghur script.

(22) Tüfawla ñi pu ñawe zeumalkefiñ lien ruka

Ka kürüf negvmüñ ma meke enew ñi logko

For my daughters I build the house of silver

As I ride my horse above the rainbow

—Elicura Chihuailaf (Mapuche, Chile)

Mapuche or Mapudungun comes from Mapu “earth, land” and Dungun “speak, speech.” It is spoken by the Mapuche people in Chile and Argentina. It is both an endangered language and a language isolate, related to no others. This line is part of a poem titled “For I am the Power of the Nameless,” found in ÜL Four Mapuche Poets, edited by Cecilia Vicuña and translated by John Bierhorst. Chihuailaf is the best known of the Mapuche poets and an advocate of preserving Mapuche as one of the “principal means of achieving dignity, of preserving and restoring for– and by – our own selves the soul of our people.”

(23) Bolibissa nashinenak, Bolibissa nashinenak,

Yako mente ay bish koko

Strawberry Moon

Strawberry Moon

Here comes the robin

—Grayhawk Perkins, Mezcal Jazz Unit (Mobilian Trade Language, Mobile Alabama)

Mobilian Trade Language was a pidgin used as a lingua franca among Native American groups living along the Gulf of Mexico around the time of European settlement of the region. It was the main language among Indian tribes in this area, mainly Louisiana. The band was formed when Garyhawk Perkins, a member of the Choctaw and Houma tribes of the Muskogee Indian Nation met the Mezcal Jazz Unit, a Cajun Jazz Band in New Orleans.

(24) Ca nyur tung thiangɛ, ca lec nyang tuoth kɛ lied

I sat on the deer's horn and

Cleaned the crocodile's teeth with sand

—Martha Kier (Nuer, South Sudan)

This line is from a traditional clapping song titled “Cleaned the Crocodile's Teeth,” translated by the poet Terese Svoboda. Nuer is one of eastern and central Africa’s most widely-spoken languages, and is spoken by the Nuer people of South Sudan and in western Ethiopia. The 2015 edition of the Ethnologue cites the number of speakers at 890,00. The Nuer people are the largest ethnic group in South Sudan but tens of thousands of Nuer have immigrated throughout the world as a result of the civil war there. Terese Svoboda is an American poet, writer and filmmaker raised in Alaska, who, after translating the songs of the Nuer people on a PEN/Columbia Fellowship, founded a scholarship for Nuer high school students in Nebraska.

(25) Kanyiṉupula aaa, maa paarrpakaṉu

Kankarra kankarra kankarrapula maa yanu uuu

Kankarra ngaatja yilkarikutu, ngurukutunga ngaatja

Then a giant eagle snatched them up

High into the sky

Up there, in the blackness

—Minnie Napanangka Daniels [Kumentji], (Pintupi, Australia)

The Pintupi are an Australian Aboriginal group who are part of the Western Desert cultural group and whose homeland is in the area west of Lake MacDonald and Lake Mackay in Western Australia. With 1500 speakers, Pintupi is one of the healthier Aboriginal languages and is taught to local children in schools. Revitalization work is being done by the Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi Aboriginal Corporation (Waltja), which is an Aboriginal-controlled, community-based organization, doing good work with families and grounded in strong culture and relationships. They work in remote Central Australian Aboriginal communities, across nine languages and across more than one quarter of the Northern Territory. "Waltja Tjutangku Palyapayi" is in the Luritja language.

We are indebted to Ken Hansen for this translation of Minnie Napanangka Daniels’ work.

(26) Gosa mii johtit go biegganjunni ii šat deaivva davás?

Where do we go when even

The lead reindeer has lost its way?

—Sofia Jannok (Northern Saami, Sweden)

This line is from a song titled “Davádat/ Westbound Wind” by acclaimed Saami performer Sofia Jannok. The song appeared on her 2010 music album “Áššogáttis/ By the Embers.” In the past decade, Saami youth have embraced their own Saami pop idols. This is a encouraging example that the Saami (or Sámi) language, spoken by about 30,000 people today in Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Russia, may well survive. Other Saami artists include twenty‐year old Mikkal Morottaja a.k.a. MC Amoc who performs rap and hip‐hop in Inari Sámi, and 22‐year old Tiina Sanila who has released the first-ever rock album in Koltta Sámi. Translation by Siri Gaski.

LOVE

(27)

A little bit of musk

She sends out

A little bit of musk.

—Peter Cook (American Sign Language, U.S.)

ASL Poet Peter Cook is an internationally acclaimed performing artist, whose works incorporate American Sign Language (ASL), pantomime, storytelling, acting, and movement. He is co‐founder of the ASL poetry troupe Flying Words, which is credited with having influenced the history of ASL poetry, with hearing coauthor Kenny Lerner, who collaborated on the line above. ASL is one of 137 deaf sign languages listed by the Ethnologue. Estimates vary significantly, but it is possible that ASL is being used by 500,000 to 2 million people in the U.S, including children of deaf adults (CODAs). This line comes from the "shot" series by Peter Cook & Kenneth Lerner (Flying Words), featured in the movie DeAf Jam.

(28) Ngabi karlu nganurr(i)y(i)nurriying

Ngabi karlu nganurri(i)yinu'

Ngabi duwa [ya] [y]abanajuku[yu]n ngadburr(i)yinurr(i)yin

I'm not going to have a shower

I'm not going to have a shower

I'm going to wait for her

And we'll have a shower together

—Ronnie Waraludj (Iwaidja, Australia)

Iwaidja is an indigenous language spoken in northern Australia by about 150 people (2006) and listed by the Ethnologue as threatened. This line is from a song titled “Ngadburriyinurriying,”written and performed by Ronnie Waraludj and translated by Nicholas Evans for the music album “Jurtbirrk: Love Songs from Northwestern Arnhem Land,” which won the Northern Territory (Australia) Traditional Music Award in 2005. Jurtbirrk (love songs) are performed informally for entertainment and may include dancing. One or two men sing the songs and play arrilil (clapsticks), while another man plays ardawirr (didjeridu).

(29) Orishen, Orishen, Orishen,

Yippen, Yippen.

Beautiful, beautiful, beautiful

Disgusting, disgusting

—Cecilia Vicuna (Selk’nam, Chile)

Cecilia Vicuña is a Chilean poet, artist, filmmaker and political activist whose work addresses topics such as ecological destruction, cultural homogenization, and economic disparity, particularly the way in which such phenomena disenfranchise the already powerless. Here she retells a story from Anne Chapman’s recordings of Lola Kiepja, the last Selk’nam shaman. Selk'nam was spoken by the Selk'nam people in Isla Grande de Tierra del Fuego in southernmost South America. Part of the Chonan languages of Patagonia, Selk'nam is extinct by most accounts, due both to the late 19th-century Selk'nam genocide by Chilean and Argentine colonizers, high fatalities due to disease, and disruption of traditional society. One source states that the last fluent native speakers died in the 1980s but another claims that two speakers had survived into 2014.

(30) Armahaizeni, kačo. Lopen sinun ke

Kaččuo sinun silmih

My love, I want to come with you

And watch your eyes

—Santtu Karhu (Karelian, Russia)

This line comes from a traditional Karelian folk song, as performed by Santtu Karhu, one of Karelia’s most famous musicians. Karelian is spoken mainly in Karelia, northwest Russia, as well as Finland, by 35,600 people. It is a Finnic language that has three main varieties, each with several dialects, some of which are not mutually intelligible. Of these varieties, Olonets Karelian and Lude have been written since 2007 using a Latin‐script based alphabet called “the modern unified Karelian alphabet,” which replaced the previous different writing systems, while Tver Karelian is written in a Latin‐script based alphabet dating to 1930. Translation is by Santtu Karhu.

(31) Ndaani’ ladxidua'ya'. Ti diidxa' si ñabe lii lu

Ti diidxa' si, ti diidxa' ma' biaanda' naa

In my heart,

Just one word to say to you in bed

Just one word

A word, I have already forgotten

—Víctor de la Cruz (Isthmus Zapotec, Mexico)

Isthmus Zapotec is one of the Zapotec languages, a group of closely related indigenous Mesoamerican languages spoken in Mexico by about half a million Zapotec people. This line is from a poem titled “The Word I Have Forgotten” by Víctor de la Cruz (b.1948) and translated by Donald Frischmann. The translator notes that in his conversations with the poet and his peers, “the theme of nostalgia… emerges. During their periods of residence in Mexico City, writing in Zapotec served to dispel the dark feelings engendered by the distance from the Mother Tongue and their Isthmus homeland.”

DEATH

(32)

This is what I was thinking of

As I sat outside today

—Dr. Erma Lawrence (Haida, Canada)

Haida is spoken in British Columbia and Alaska. It is a language isolate, related to no others, and has about 55 native speakers left. Dr. Erma Lawrence (1912‐2011) wrote, edited, and participated in publishing many Haida language books, including a Haida‐to‐English and English‐to‐Haida dictionary, published in 1977 by the Society for the Preservation of Haida Language and Literature, of which she was a founding member. Dr. Lawrence’s Haida name is Áljuhl, meaning “Beautiful One.” She devoted her life to gathering, recording, documenting, and teaching Haida.

(33) кандыг болган ындыг арткан сен

сен миим эджим эки эджим

кандыг ырааган сен миим эджим

The way you were is how you remained

You my friend, my good friend

What have you done

Oh why have you gone far away

—Lydia Stepanovna Bolxoeva (Tofa, Russia)

Tofa (also Karagas) is mostly oral, and employs a Cyrillic alphabet when written. It is one of the Turkic languages, spoken by about 100 people in Russia today, and is listed by the Ethnologue as nearly extinct. These lines were sung in 2001 by Lydia Bolxoeva and recorded by K. David Harrison. This song is published on National Geographic’s "Enduring Voices" YouTube Channel. Along with other published endangered languages recordings, they serve to foster collaboration between academics and communities to promote language revitalization. Lines translated by Greg Anderson and K. David Harrison.

(34) Ne hinwanye wotourou biye wo mone esdoula

When a man dies

It is not a good thing to be alone

—Djangounon Dolo (Dogon, Africa)

The Dogon languages are a small, close-knit language family spoken by the Dogon of Mali, which are generally believed to belong to the larger Niger–Congo family. There are about 600,000 speakers of around fourteen languages. The Dogon consider themselves a single ethnic group, but recognize that their languages are different.

(35) Dame le gien nowen wanwa, lauba gien banda habunana

When I pass to my final resting place

An official marching band will lead me

—Paul Nabor (Garifuna, Belize)

This line comes from a song titled “Naguya Nei/ I Am Moving On” by Paul Nabor (1928-2013), a parandero, or old master of the Paranda music style, and an abuyei, a spirit medium and healer who attends to his congregation at a Garifuna temple he built in Punta Gorda. He wrote it for his sister when she was on her deathbed. The language, dance, and music of the Garifuna people were included in UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008. Of the 600,000 people who identify as having Garifuna heritage, it is estimated that the language is spoken by at least 190,000, living in Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, as well as in New York City, Los Angeles and New Orleans.

(36)

I’m coming back tomorrow

—Clifton Bieundurry (Walmajarri Hand sign, Australia)

Many Australian Aboriginal cultures have or traditionally had a manually coded language, a signed counterpart of their oral language. This appears to be connected with various speech taboos between certain kin or at particular times, such as during a mourning period for women or during initiation ceremonies for men. Clifton Bieundurry is a Walmajarri artist from the Central Kimberley region. He spent his formative years immersed in traditional language and cultural practices in his family homeland.

(37) Ka mate! Ka mate! Ka ora! Ka ora!

I die, I die

I live, I live

—Te Rauparaha (Māori, New Zealand)

Te Rauparaha (c.1768?-1849) was a chief of Ngāti Toa, a New Zealand Māori tribe and an influential character in New Zealand history. He is remembered as the author of the haka “Ka mate,” which he composed when he escaped from his enemies after a defeat in battle. The poem is a celebration of life over death. It has also traditionally been performed by two of New Zealand’s international rugby teams on the field, immediately prior to international matches. A haka is a traditional ancestral war cry, dance, or challenge of the Māori people of New Zealand.

WORDS

(38)

If you feel the words you use are useless

Let them be your escape into the Truthful

These words that say,

“I do exist”

—Sriman Nayaki Swamigal (Sourashtra, India)

Saurashtra is spoken by about 200,000 people in southern India. Although it has its own written script, few people know how to read and write in it and speakers alternatively use Latin, Devanagari, or Tamil scripts for writing. India has several hundreds of individual Mother Tongues. The 2001 Census of India notes 30 languages spoken by more than a million native speakers and 122 by more than 10,000 people. Translation by Savithri N. Rajaram, with Steve Zeitlin and Bob Holman.

(39) Hizkuntza batek ez du hormarik eraikitzen, kolorez pintatzen ditu

A language builds no walls,

It paints them in colors

—Kirmen Uribe (Basque, Spain)

Basque, a language isolate spoken by about 700,000 people today, is the language of the Basque ethnic group, which primarily inhabits parts of northern Spain and southern France. The language has been a tumultuous political issue as the Basques advocate for independence, and as the Spanish and French governments have attempted to restrict the use of the language historically and still today. Kirmen Uribe (b.1970) is a renowned Basque‐language poet, author and performer born in Ondarroa, Basque Autonomous Community, Spain. Translation is by Elizabeth Macklin.

(40) Na kumeh for madi koe fineh: Ar For! Ar Neh for

When something is hard to say,

“Say it” they tell the poet, and he says it!

Say it!

—Momory Finah (Kuranko, Sierra Leone)

Kuranko is spoken by about 300,000 people in West Africa, mainly in Sierra Leone, but also in Guinea and Guinea‐Bissau. Momory Finah is a Finah poet from the village of Dankawali in Northeast Sierra Leone. In Kuranko a Finah is a poet/storyteller/master of ceremonies who works without music and almost always in an Islamic context. The translator, Kewulay Finah Kamara, is a Sierra Leone immigrant to the U.S.– he is also a Finah poet. Kamara produced a documentary film, In Search of Fina Misa Kule, with City Lore's Steve Zeitlin about his journey back to Africa to recreate an ancient epic handed down in his family, the only written copy of which was destroyed in the recent civil war in Sierra Leone.

(41) Hayutke hvtke

White Dawning

—Joy Harjo (Mvskoke, U.S.)

Mvskoke, anglicized as Muscogee, is spoken by about 6,000 of the 52,000 Muscogee Native American people (statistics of 2007 and 1997 respectively) who live in states of Oklahoma, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. Muscogee is a threatened tongue– there are 45 monolingual speakers. This line is from a song titled “Winding through the Milky Way,” written and translated by Joy Harjo, an award‐winning poet, author, and musician, and comes from her album Red Dreams, A Trail Beyond Tears.

(42) ئەگەر تىنىچلىق قىلسا تەلەپ قان تۇكۇشنى تىنىچلىختىكى ئۇ گۇزەللىكمۇ كېتىدۇ ئۇلۇپ

If peace requires blood

Then there will never be peace

—Aisha Kashgari (Uyghur, China)

Uyghur is a Turkic language with about 9 million speakers who live primarily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of Western China. This line, inspired by Sufi thought, was written by the 17th century poet Shah Mäshräp and is performed within the Čahargah Maqäm, one of the Twelve Maqäms, or musical suites, of Uyghur music. The Mäshräp songs comprise one section of the Twelve Maqams and are also part of the Sufi repertoire, which are performed ritualistically in addition to being sung in bazaars and at shrine festivals. Aisha Kashgari is a Uyghur poet who divides her time between China and the US.

(43) Ni eiya, yaah ni

In one breath, earth and sky together

—Rex Lee Jim (Navajo, Navajo Nation)

This poem was written and translated by Rex Lee Jim, an author, playwright, and medicine man, who is currently Vice President of the Navajo Nation. Jim played a key role in the drafting and passage of the International Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2007. He proposes an alternative translation based on the sounds of the words: “you you are/ awe/ is yours.” Navajo is spoken in the southwestern United States and has more speakers than any other Native American language north of the U.S.‐Mexico border, numbering around 170,000.

(44) Wolaki yoobi guddu idanna kolay shijju baisiye

Kayoobkiye aiki roo takto

Let's come together right away

And talk about all this

—Kurayo Gurao (Ongata, Ethiopia)

Ongota is a moribund language of southwest Ethiopia. UNESCO reported in 2012 that out of a total ethnic population of 115, only 12 elderly native speakers remained, the rest of their small village on the west bank of the Weyto River having adopted the Ts'amakko language instead. The main mechanism behind the decline of Ongota is marriage with other communities, in particular the Ts'amakko. In a brief expedition in the early 1990s, a number of researchers made the observation that many Ongota men married Ts'amakko women. The child would grow up speaking only the mother's language, but not the father's.

(45) Boham

Mi yecah lēaqam c’ēwulehkila, ‘olēaqu!

K’ilepnāmena ‘ih!

Hō.

Hello

If you can speak a Native language, speak up!

Don’t be afraid to do it

Ho!

—Rick and Cody Pata (Nomlaki, California)

The Nomlaki language was traditionally spoken in the Sacramento Valley from Cottonwood Creek in the north to Grindstone Creek in the south, from the banks of the Sacramento River in the east, to the peaks of the Coast Range in the west. In pre-contact times, it is conservatively estimated that there were 12,500 speakers of Nomlaki, Patwin, and Wintu together. Today, there is only one Nomlaki language speaker. Nomlaki (also known as "Central Wintun") is a Wintuan language; the other Wintuan languages are Patwin and Wintu. Together, these languages form one branch of the hypothesized Penutian language family. Cody Pata is Nommaq Nomlāqa Wintūn. His family comes from the Paskenta region of Tehama County, California. Cody is the last proficient speaker of the Nomlāqa language. This line was created as part of the Native Language Challenge, set up by Vincent Medina of the News From Native California.

(46) Chamu Chamu ye tu

Talk some, leave some

—Isaac Bernard (Kromanti, Jamaica)

Kromanti is a ritual language used by the elderly in Moore Town, Portland, Jamaica. This West African language survived among runaway slaves in the 17th century, remaining in use for everyday communication till the 20th century. It is threatened today because of traditions of secrecy and low interest on the part of younger Jamaicans to learn it. However, in 2003, Moore Town heritage was named a UNESCO Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in an attempt to safeguard it. The line was translated by Hubert Devonish.

(47)

Now we've finally had a good conversation

—Lalit Bahadur (Thangmi, Nepal)

Thangmi is a Tibeto‐Burman language of Nepal, spoken by about 25,000 people and classified by the Ethnologue as threatened. This line was recited by the Thangmi guru Lalit Bahadur at a wedding in 2005 and translated by Sara Shneiderman and Bir Bahadur Thami. A Thangmi wedding is preceded by asking for the bride’s hand by the groom’s family. It takes a minimum of one year of preparations before the wedding takes place. During that time, several rites are completed and specific offerings are made from the groom’s family to that of the bride.

(48)

Welcome to our language

Taste the sauce!

—Reesom Haile (Tigrinya, Eritrea)

It fits that the last line of “Khonsay” was written by Reesom Haile (1946‐ 2003). Haile returned to Eritrea after twenty years abroad, during which he taught Communications at The New School for Social Research in New York and worked as a Communications Consultant with UN Agencies, governments, and NGOs around the world. His work sets an example for working with poetry to retain and safeguard local languages and cultures while integrating them into the global culture. Tigrinya is a Semitic language spoken in Eritria and Ethiopia. These lines are from a poem titled “Our Language,” and translated by Charles Cantalupo.

Khonsay is part of a larger project focusing on endangered languages by the nonprofit organizations Bowery Arts + Science and City Lore. Khonsay was conceived by Bob Holman and Steve Zeitlin, directed by Bob Holman, and co-produced with Molly Garfinkel. It was realized with contributions from endangered language poets, singers, translators, and linguists from around the world, with the help of Catherine Fletcher, Emilie Arrighi, Maya Alkateb, Puja Sahney, and Zsuzsanna Cselenyi. A booklet of an early of Khonsay was published in conjunction with the Khonsay exhibit at the 2013 Smithsonian Folklife Festival in Washington D.C., edited by Maya Alkateb and Bob Holman. This website was created by John Priest and updated by Sam O'Hana.

Appendix: Language status

The 13 levels of language statuses are formally known as the Expanded Graded Intergenerational Disruption (EGIDS) Scale, developed by Lewis and Simons in 2010, and used by the Ethnologue.

Starting at the level “threatened” through “dormant,” the labels above apply to endangered languages and stress the crisis those are passing through. When language revival efforts are undertaken, parallel, more optimistic terms are used: “threatened” becomes “re-‐established,” “shifting” becomes “revitalized,” “moribund” becomes “reawakened,” “nearly extinct” becomes “reintroduced,” and “dormant” becomes “rediscovered.”

International

The language is widely used between nations in trade, knowledge exchange, and international policy.

National

The language is used in education, work, mass media, and government at the national level.

Provincial

The language is used in education, work, mass media, and government within major administrative subdivisions of a nation.

Wider Communication

The language is used in work and mass media without official status to transcend language differences across a region.

Educational

The language is in vigorous use, with standardization and literature being sustained through a widespread system of institutionally supported education.

Developing

The language is in vigorous use, with literature in a standardized form being used by some though this is not yet widespread or sustainable.

Vigorous

The language is used for face-to-face communication by all generations and the situation is sustainable.

Threatened

The language is used for face-to-face communication within all generations, but it is losing users.

Shifting

The child-bearing generation can use the language among themselves, but it is not being transmitted to children.

Moribund

The only remaining active users of the language are members of the grandparent generation and older.

Nearly Extinct

The only remaining users of the language are members of the grandparent generation or older who have little opportunity to use the language.

Dormant

The language serves as a reminder of heritage identity for an ethnic community, but no one has more than symbolic proficiency.

Extinct

The language is no longer used and no one retains a sense of ethnic identity associated with the language.

References by poem line number

The Ethnologue was checked during May and June 2013 for cited numbers of languages’ speakers.

Introduction: Thanks to Mark Abley for inspiring the title "Khonsay," which was found in his book: Abley, M. (2003). Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company.

1. Dauenhauer, N. M. (1988). The Droning Shaman: Poems. Haines, AK: The Black Current Press. 87, 93. Dauenhauer, N. M. (2000). Life Woven with Song. Tuscon, AZ: The University of Arizona Press. 139.

2. Montemayor, C., & Frischmann, D. (Eds.) (2005). Words of the True People: An Anthology of Mexican Indigenous-Language Writers (Vols. 2). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. xv, 215, 229.

3. Council of Aboriginal Elders of SA INC. (n.d.). Aboriginal Aged Care Program. Retrieved June 5, 2013,

4. Poetry Foundation. (n.d.). Ofelia Zepeda. Retrieved June 6, 2013, from http://www.poetryfoundation.org/ bio/ofelia-‐zepeda

Zepeda, O. (1982). Ju:ki/ Rain. Retrieved June 6, 2013, from http://www.hanksville.org/voyage/ rain/rain1pap.php and http://www.hanksville.org/voyage/ rain/rain1.html

5. Uata, J. (2011, September 28). Moana Love: Poet, Actor, Painter Vaimoana Niumeitolu.

TheWhatItDo.com Urban Island Review. Retrieved June 11, 2013, from http://www.thewhatitdo.com/201 1/09/28/moana-‐love-‐poet-‐actor-‐ painter-‐vaimoana-‐niumeitolu/

6. C. Lo, personal communication to M. Alkateb, June 7, 2013. E–mail.

Devineni, R. (Editor), Devineni, R., & Seigne, B. (Producers). (2012). On the Road with Bob Holman: A Poet’s Journey into Global Cultures and Languages [Film]. New York, NY: Rattapalax Productions. 3:50-‐ 4:00, 7:34-‐7:45, 11:14-‐11:21.

7. Monintja, R. (2013) “The Story of Lumimuut and Toar”, Public Radio International, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_6atnYk7__I

‘Tontemboan’, Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 449

“When New Yorker Rose Monintja speaks her native tongue, the memories flood back”. PRI. Retrieved 20:59, July 5th, 2016, from http://www.pri.org/stories/2013-10-10/when-new-yorker-rose-monintja-speaks-her-native-tongue-memories-flood-back

8. Baldisseri, G. G. (2011). Rhythms from the Heart. New York, NY: Tinig Mamamayan Press. 24.

De Yro, B. S. (2012, October 16). DepEd indigenous culture revival in upswing. Philipine Information Agency. Retrieved May 21, 2013 from http://www.pia.gov.ph/news/inde x.php?article=2181350359825

9. Liebhaber, S. (2011). The Diwan of Hajj Dakon: A Collection of Mahri Poetry. MA: American Institute for Yemeni Studies. 160.

Mahri Poetry Archive (n.d.). Mahri Poetry Archive. Retrieved June 4, 2013 from http://sites.middlebury.edu/mahri poetry/publishedpoems/diwanhajj dakon/poems-‐by-‐hajj-‐dakon/8-‐ ḥom-‐lekteb-‐ḫaṭ-‐i-‐want-‐to-‐write-‐a-‐ line/

Morris, M. (n.d.). Book Review: The Diwan of Hajj Dakon: A Collection of Mahri Poetry. The British-‐Yemeni Society. Retrieved June 3, 2013 from http://www.al-‐ bab.com/bys/books/liebhaber12.ht m

10

‘Ohlone’ Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 315.

Ohlone Languages. Retrieved 21:01, July 5th, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ohlone_languages

11

Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. (n.d.). 20 Year Strategy for the Irish Language 2010-‐2030. Retrieved June 6, 2013, from http://www.ahg.gov.ie/en/20YearStrategyfortheIrishLanguage/

Irish language. (2013, May 30). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:34, June 4, 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.p hp?title=Irish_language&oldid=557 574281

12

Languages of Democratic Republic of the Congo: An Ethnologue Country Report. Ethnologue: Languages of the World.

13

Creole language. (2013, May 16). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:13, June 4, 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.p hp?title=Creole_language&oldid=5 55295923

Laraque, P., & Hirschman, J. (2001).

Open Gate: An Anthology of Haitian Creole Poetry. Willimantic, CT: Curbstone Press. 188, 189, 232

14

Hawaiian Music Hall of Fame. (n.d.). Keaulumoku. Retrieved June 15, 2013, from http://www.hawaiimusicmuseum. org/honorees/1995/keaulumoku.h tml

P. Nogelmeier, personal communication to B. Holman, May 3, 2013. E-‐mail.

W. Willson, personal communication to B. Holman, May 3, 2013. E-‐mail.

V. Takamine, personal communication to S. Zeitlin, January 20, 2011. E-‐ mail.

15

A. Atuire, personal communication to M. Alkateb, sharing from the oral tradition of the Bulsa of northern Ghana, June 13, 2013. E-‐mail.

Laube, W. (2007). Changing Natural Resource Regimes in Northern Ghana: Actors, Structures and Institutions. Berlin: Lit Verlag. 114

16

Oneida Language. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:04, July 5th, 2016, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oneida_language

Maria Hinton Obituary. Ryan Funeral Home and Crematory. Retrieved 21:06, July 5th, 2016, http://www.ryanfh.com/obituary/Maria-A.-Hinton/Oneida/1229136

17

Countries and Their Cultures. (n.d.). Mekeo – Religion and Expressive Culture. Retrieve June 12, 2013, from http://www.everyculture.com/Oce ania/Mekeo-‐Religion-‐and-‐ Expressive-‐Culture.html

I.Rayan, personal communication to M. Garfinkel, April, 2013.

18

Nǁng language. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:07, July 5th, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N%C7%81ng_language

C.Collins, personal communication to B. Holman, September 2016.

19

‘Inuktitut’ Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p.250.

Inuktitut language. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:09, July 5th, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inuktitut

20

‘Tsou’ Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 528.

Tsou language. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:14, July 5th, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tsou_language

21

‘Manchu’, Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 348.

Manchu language. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:21, July 5th, 2016. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manchu_language

22

‘Mapuche’, Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 254.

C. Vicuña, personal communication with B. Holman, September 2016.

23

Mobilian Jargon. (2013, April 25). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:22, July 5th, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mobilian_Jargon

24

Nuer people. (2013, May 19). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:05, June 10, 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.p hp?title=Nuer_people&oldid=5558 15274

Nye, N. S. (Ed.). (2008). This Same Sky: A Collection of Poems from Around the World. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. 115.

Svoboda, T. (Translator). (1985).

Cleaned the Crocodile’s Teeth: Nuer Song. Greenfield Center, NY: The Greenfield Review Press. 61.

25

‘Pintupi’ Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 589.

Pintupi Dialect. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:25, July 5th, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pintupi_dialect

K. Hansen, personal communication with B. Holman, September 2016.

26

Jannok, S. (2010). Davádat (Westbound Wind). On Áššogáttis (By the Embers) [CD]. Spring, TX: AIS. (2007-‐2008)

Kauhanen, M. (2005). Something New From Something Old. Finnish Music Information Center FIMIC. Retrieved May 23, 2013 from http://www.fimic.fi/fimic/fimic.nsf /0/D9DD8F7B42B343C3C225750C0 041E116?opendocument

27

Mitchell, Ross; Young, Travas; Bachleda, Bellamie; Karchmer, Michael (2006). "How Many People Use ASL in the United States?: Why Estimates Need Updating". Sign Language Studies. Gallaudet University Press. ISSN 0302-1475. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

DeafPeterCook.com. (n.d.). Peter S. Cook, and Flying Words Project. Retrieved June 13, 2013, from http://www.deafpetercook.com/h ome/Peter_S._Cook.html and http://www.deafpetercook.com/h ome/Flying_Words_Project.html

Lieff, J. (2011). Deaf Jam [Film]. New York, NY: City Lore and Independent Television Service (ITVS) (Producers). 02:02:39.

28

Waraludj, R. (2005). Ngadburriyinurriying. On Jurtbirrk: Love Songs from Northwestern Arnhem Land [CD]. Batchelor, NT: Batchelor Press.

Iwaidja Inyman. (n.d.). Jurtbirrk: Love Songs from Northwestern Arnhem Land. Retrieved June 11, 2013, from http://www.iwaidja.org/site/jurtbir rk/

29

Selk’nam People. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20:12, June 29th, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Selknam_people

Cecilia Vicuña. In The Poetry Foundation. Retrieved 20:27, June 30th, 2016,

from http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/cecilia-vicuna

30

Karelian language. (2013, April 30). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 04:12, June 16, 2013,

from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/in dex.php?title=Karelian_language& oldid=552845812

Karhu, S. (2005). Livvin Kielellä [DVD]. Oulu: Quetzalcoatl Production Ltd. 24:45.

31

Montemayor, C., & Frischmann, D. (Eds.) (2005). Words of the True People: An Anthology of Mexican Indigenous-‐Language Writers (Vol. 2). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. 21, 43, 46, 47.

32

Kasaan Haida Heritage Foundation (2004, Fall). Erma Lawrence Awarded Honorary Doctorate. Kasaan Haida Heritage Foundation. Retrieved June 7, 2013, from http://www.kavilco.com/khhf_nws ltrs/2004-‐khhf-‐nws.pdf

Kavilco Archivist. (2012, August 31).

Baronovich Family Collection [Pecasa Web Album]. Retrieved June 7, 2013 from https://picasaweb.google.com/110 919211263172816552/Baronovich FamilyCollection

Olsen, F. O., Jr. (Director, Producers). (2007). Surviging Sounds of Haida

[Film]. Seattle, WA: Kasaan Haida Heritage Foundation. 2:37-‐2:43. Retrieved June 6, 2013, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v =HBjx5_cMPpw&feature=related

33

Enduring Voices. Lydia Bolxoeva, A Last Speaker of Tofa, Sings [Video]. Retrieved June 12, 2013, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v =Oi0Hp3rhIa0

34

‘Dogon’ Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 153.

Dogon languages. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20:34, July 5th, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dogon_languages

35

Frontline World. (2004, January). Priest and Poet: Paul Nabor: Paranda. PBS, New York. Retrieved June 16, 2013, from http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld /stories/belize/nabor.html

36

Australian Aboriginal sign languages. In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20:38, July 5th, 2016, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_Aboriginal_sign_languages

Clifton Bieundurry. In NOMAD: Two Worlds. Retrieved 20:37, July 5th, 2016, from https://nomadtwoworlds.com/art-gallery/australia-collection/clifton-bieundurry

37

Haka. (2013, June 4). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:22, June 11, 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.p hp?title=Haka&oldid=558345267

Ka Mate. (2013, April 25). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21:15, June 11, 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.p hp?title=Ka_Mate&oldid=5520861 35

Sullivan, R. (2006). Ka Mate, Ka Ora: I Die, I Live. Ka Mate Ka Ora: A New Zealand Journal of Poetry and Poetics, 1. Retrieved June 11, 2013, from http://www.nzepc.auckland.ac.nz/ kmko/01/ka_mate01_sullivan.asp

38

Languages of India. (2013, June 15). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved 05:27, June 16, 2013, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/in dex.php?title=Languages_of_India &oldid=560029924

Natanagopala, N., & Srinivasaraghavan, A. (1970). Divine Kritis of Sriman. Natanagopala Nayaki Swamigal: A great bridal mystic, in Sourashtram. Madurai: Siddhasramam.

39

Filologia, E. (2007, July 3). Hizkuntza [Txutxumutxu Blog Entry]. Retrieved June 5, 2013 from http://www.blogari.net/txutxumut xu?blog=1562&cat=4962&page=1 &disp=posts&paged=3

Uribe, K. (2007). Meanwhile Take My Hand. Saint Paul, MN: Greywolf Press. 71.

40

Kamara. K. (Director). (n.d.). In Search of Kewulay Finah Kamara [Film]. In production by City Lore.

Rosenblum, C. (2011, October 6). Where Stories Are Remembered. The New York Times. Retrieved June 10, 2013, from http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10 /09/realestate/jackson-‐heights-‐ queenshabitats-‐where-‐poetry-‐is-‐ remembered.html?_r=1&adxnnl=1 &adxnnlx=1370895860-‐ aaVu9fBl3QdzdmGRY+hlLw

41

Harjo, J. (2008). Winding Through the Milky Way. On Red Dreams, A Trail Beyond Tears [CD]. Portland, OR:

CD Baby (distributor). (2010)

42

Harris, R. A. (2008). The Making of a Musical Canon in Chinese Central Asia: The Uyghur Twelve Muqam. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing Limited. 63-‐65.

43

Navajo Nation Department of Information Technology. (n.d.). Ben Shelly, Rex Lee Jim: Navajo Nation President and Vice President. Retrieved June 15, 2013, from http://www.president.navajo-‐ nsn.gov/vicePresident.html

Videoforpaw. (Uploaded 2010, October 28). Rex Lee Jim ’86 [Video]. Retrieved June 12, 2013, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?f eature=player_embedded&v=Pk6E SQUmxm8

44

‘Ongota’ Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition. p. 126.

G. Sava, personal communication with B. Holman, September 2016

45

Nomlaki. In Survery of California and Other Indian Languages. Retrieved 20:48, July 5th, 2016 http://linguistics.berkeley.edu/~survey/languages/nomlaki.php

46

The Jamaican Language Unit (Producer). (2009). Tongues of Our Fathers: Kromanti [Film]. Mona: The University of the West Indies at Mona, Jamaica. 4:06, 10:34. Retrieved June 11, 2013, from http://www.youtube.com/watch?f eature=iv&v=TBKoDaR12UQ&anno tation_id=annotation_436637

The University of the West Indies at Mona, Jamaica. (n.d.). Garifuna and Maroon proclaimed by UNESCO as “Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.” Retrieved June 11, 2013, from http://www.mona.uwi.edu/dllp/jlu/ciel/pages/kromanti.htm

47

S. Shneiderman, personal communication to B. Holman and M. Garfinkel, March 7, 2011. E-‐ mail.

Shneiderman, S., Thami, B. B., Turin, M., & Khadka, H. (n.d.) Thangmi Wedding Rituals: A Translation and Analysis. Manuscript submitted for publication.

48

Cantalupo, C. (1999). Preface to “We Have Our Voice”: A Bilingual Edition of Selected Poetry by Reesom Haile with Charles Cantalupo. Retrieved May 29, 2013 from http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/hai le/hailepre.htm

C. Cantalupo, personal communication to B. Holman, June 18, 2013. E-‐mail.

Haile, R. (2001). Our Language. The People’s Poetry Gathering, March 30-‐ April 1, back cover.

Young, K. (1999). Reesom Haile: Prophet of the Global Village. Retrieved May 29, 2013 from http://www.thing.net/~grist/ld/hai le/ky-‐reesm.htm

Appendix

Lewis, M. P., Simons, G. F., & Fennig, C. D. (Eds.). (2013). Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 16th Edition.

Dallas, TX: SIL International. Online page: Language Status. Retrieved on June 15, 2013, from http://www.ethnologue.com/about/la nguage-‐status

Khonsay was stitched together from every source we could find, and we have done everything possible to give proper credit. Please let us know if you see any information that needs correcting.